While the corpses of migrants who died during Sunday’s boat disaster are still washing ashore together with few survivors, and a special EU council meeting today debates ever more repressive border controls across the Mediterranean, media reports the arrest of a ruthless racket of human traffickers that is apparently tearing a gaping hole in Europe’s border control policies. An enquiry into the business of migration.

While the corpses of migrants who died during Sunday’s boat disaster are still washing ashore together with few survivors, and a special EU council meeting today debates ever more repressive border controls across the Mediterranean region today (but read this document for a concrete rebuffal of the EU’s confidential draft, which includes, amongst others, the systematic tracking and destruction of smuggling vessels –a sheer impossibility– as well as a more structural assistance to Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, Mali and Niger to combat ‘irregular migration’ –which very likely opens the door to more human rights abuses), media reports the arrest of a ruthless racket of human traffickers that is apparently tearing a gaping hole in Europe’s border control policies.

On Tuesday Italian police arrested a 27-year-old Tunisian believed to be the captain of the sunken ship, together with his Syrian accomplice. In the meantime, a long-term investigation by the anti-mafia directorate of Palermo announced the arrest of 24 traffickers with contact points in the African Horn and North Africa, Italy and Northern Europe (particularly Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Germany), whose main aim was to facilitate illegal immigration from Africa towards Europe. Over the past few years, trafficking human beings has become big business in the Mediterranean. Competing criminal gangs are jostling for fares – “like budget airlines”, as one observer put it. Though the view of hundreds of dead bodies trapped like animals in the lower decks of Sunday’s ship evokes an imagery more reminiscent of the Titanic.

In an opinion piece for the New York Times today, Italian premier Matteo Renzi calls human traffickers “the slave traders of the 21st century” –adding that “[n]ot all passengers on traffickers’ boats are innocent families. Our effort to counter terrorism in North Africa must evolve to outpace this menace, which creates fertile ground for human trafficking and interacts dangerously with it.”

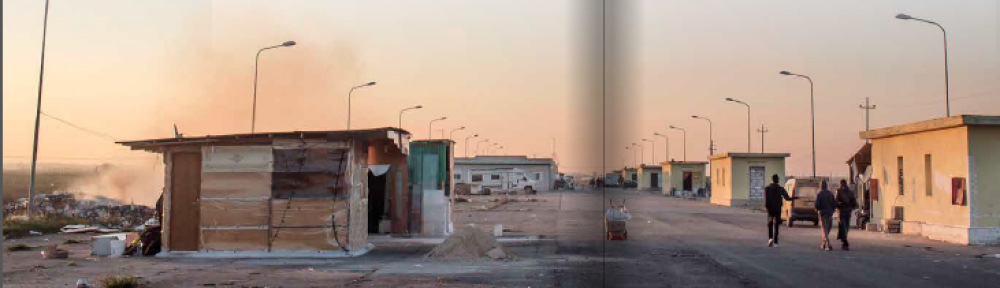

Indeed many migrants who cross the Mediterranean today are departing from Libya, where the collapse of government authority has given smugglers and human traffickers the freedom to operate with impunity.

A remarkable detail though, which I’ve seen only reported in the Italian press so far, is that quite a number of the charged traffickers were staying in the official refugee host center (CARA) of Mineo, in Sicily. From there, Eritrean and Ethiopian agents were concerned with picking up migrants in the provinces of Catania and Agrigento and sending them northwards. Mineo is the biggest official refugee host center on the Italian peninsula. Over the past two years, it has doubled its capacity from 2.000 to almost 4.000 inhabitants (37 % of the total hosted population in the country’s emergency centers). In 2011, these former US Marines army barracks were quickly refurbished for the purpose of hosting migrants and asylum seekers –including from the bursting center of the island Lampedusa. Since then, it has been working way beyond its capacities, hosting people up to 2 years in the most appalling conditions, as this video report by the Italian programme Presa Diretta shows.

Interestingly, the CARA of Mineo also figures in the recent investigation Roma Mafia Capitale. In their book (two editions sold in one week!), journalists Livio Abbate and Marco Lillo describe the center as a central kingpin of the nascent Matteo Renzi government at the time of its contract renewal in 2013-2014. The host center guaranteed the entry of the NCD (Nuovo Centro Destra) of Angelino Alfano as a key government partner through their Sicilian secretary Castiglione who –accidentally or not- functioned as the “implementing agent” of the Mineo contract. The key mediator in this affair, however, has been Luca Odevaine (or Odvaine). As a former cabinet chief of Roman mayor Walter Veltroni and president of IntegrAzione he accepted regular back payments from criminal figures of the Roman underground (amongst others former right-wing terrorist Massimo Carminati) to facilitate migrant flows towards host centers that literally generated millions of euros.

Regardless of which slave traders Renzi is talking about in his recent New York Times article, the Mafia Capitale investigation demonstrates just how far European border policy has stumbled beyond the line of usual business interests in the management of migration industries across its Southern borders. Looking backwards, this whole operation starts to look more like a form of private indirect government, as Achile Mbembe would call it, whereby various “shadow” organizations increasingly out-perform the state in many of its definitive functions. Or as Paul Veyne observed of the late Roman Empire: “When things reach this pass, it is pointless to speak of abuses or corruption: it has to be accepted that one is dealing with a novel historical formation.”

Pingback: The colour line | Liminal Geographies

Recently I stumbled upon this remarkable interview with artist John Akomfrah on Sea-Migration, Borders, and Art, which hinges upon this very topic (by Maurice Stierl): https://youtu.be/YJjkNl-tvzs