I am happy to share a blog post on my recent monograph from the editor Cornell University Press, which elaborates on another post from the Sage House Blog.

What is the social and ecological cost of eating industrialized farm products? And why should we care? In my book The Natural Border: Bounding Migrant Farmwork in the Black Mediterranean, I describe how the global agri-food industry wrecks the land and the workers engaged in the production of farm products, with the aim to accumulate capital far away from the places where food is being produced. Building on the example of the canned tomato – a typical “Made in Italy” product – and the expansion of its production along a complex chain that involves producers in Italy, distributors in Europe, and workers from Africa’s Sahel region, I argue that this contemporary agri-food frontier is based on fundamental racial and socio-ecological hierarchies.

Though Italy is famous for its excellent food (the country is the word’s third top producer of tomato commodities, after China and the US), workers in the sector don’t meet the minimum standards in terms of job safety, housing, and welfare: over one third of the 1.2 million people engaged in agriculture today are migrants from ‘new entry’ EU countries like Bulgaria and Romania, and from Sub-Saharan Africa. While their contracts are either non-existent of incomplete – and in this sense, agri-food labor remains largely informal – producers heavily rely on so-called gangmastering networks (in Italian, called caporalato), which, in return for a cut from workers’ wages, provide the paperwork and logistics to channel workers towards the exploitative farm jobs that get our daily food on the table. As one worker quoted in my book put it: “behind your food is our slavery.” Following insistent migrant protests in recent years, Italy has passed a series of legislations that make caporalato a criminal offense, not just for the illegal labor intermediaries but also for the firms that hire them. This would be good news, if it were not for the fact that the responsibility for denouncing such abusive practices continues to fall on the shoulders of the workers and their social networks. Not surprisingly, therefore, only a fraction of current abuses is being officially reported.

As one worker quoted in my book put it: “behind your food is our slavery.”

While I join the critiques of labor unions and activists against this gap in legal provisions, I take a step further in the analysis of labor exploitation, by analyzing the fundamental racial hierarchies on which the tomato labor regime is based. Adopting a long-term perspective, I highlight the reinforcing dynamics through which land and labor are being brought to fruition in the context of an expanding corporate food regime. Building on historical records of colonialism in Africa, and of Italy’s internal colonization process, I highlight how the historical division of labor between ‘nature’ and the labor invested in its commodification has generated a double discrimination. In short, industrialized agriculture submits the earth to a factor of capitalist production, while at the same time it naturalizes the spatial segregation of the agricultural workforce into a subaltern condition of marginality. In that sense, I argue, the racialization of nature, and the naturalization of racial segregation, are, really, two sides of the same coin.

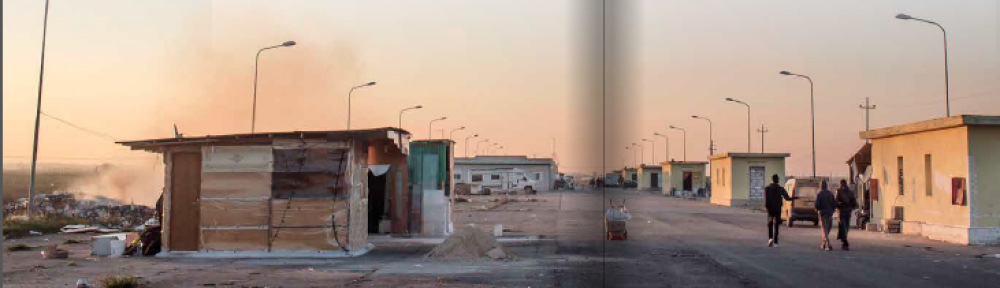

The Natural Border is also grounded in a deep ethnography of African workers’ lives as they dwell between the African Sahel and Italy’s informal rural labor camps, where they try to make ends meet, mend relations with employers, and seek to dodge Europe’s increasingly repressive bordering infrastructures. In this new, globalized rurality, it is worth asking what will be the future of agrarian societies that persist on the brink between different modes of production and reproduction, and which remain characterized by persistent state abandonment, labor exploitation, and socio-ecological depletion.

My answer lays in the Black Mediterranean: a concept that highlights the increasing, though largely marginalized and informalized, construction of places between the interconnected rural ways of life and their social and ecological reproduction across European-African boundaries. Building on the experiences of young African workers and their extended networks, I argue that the informalized infrastructures that mobilize farm labor not only provide an indirect subsidy to capital, but they also bear the potential to repoliticize a historical marginality that has characterized the expansion of rural capitalism from its very inception.