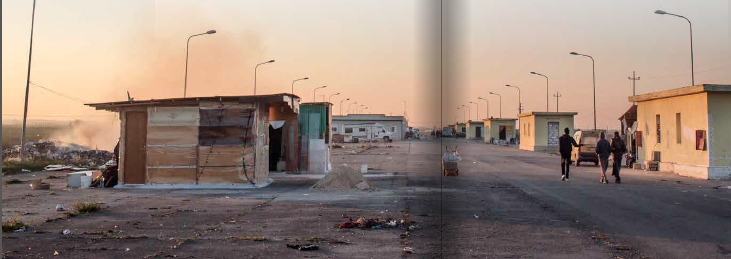

On the night of 7-8 May, a destructive fire once again hit the African ‘ghetto’ of Boreano, situated near the town of Venosa, in the province of Potenza, on the border between Puglia and Basilicata. It’s the third time in short period that an African labour settlement ends up in flames in this border region, which is also the heart of industrial tomato production in the South of Italy. The triangle of land between Puglia’s touristy coastline and Basilicata’s mountainous hinterland hosts dozens of ‘ghettos’ like this, but which usually escape the eye of visitors and the media.

(c) Marc-Antoine Frebutte

But while national media reports on these “invisible cities” remain extremely rare even during the high harvesting season, local organisations speculate highly about the causes of this damaging fire. Daniele Troia, intendant of the Methodist Church, reports the cause might have been an incident: during a short moment of distraction, a gas bottle might have ignited and caused a rapidly spreading fire. Such fires do happen regularly in these haphazardly constructed bidonvilles made of cardboard and plastic sheetings. But others suspect a more criminal cause. Aboubakar Soumahoro, of the labour union Unione Sindacati di Base, says it is no coincidence the fire happened less than a week after a meeting, which brought together about fifty labourers who had decided to effectively claim their rights for fair pay and better housing conditions. Together with the Methodist Church, USB had started to accompany some of the African farm labourers who live inside the ghetto of Boreano, according to regional authorities under the strict control of the local mafia.

On May 5, about fifty African labourers met the mayor of Venosa in the city council accompanied by USB delegates, threatening to declare a general strike. As Gervasio Ungolo and Paola Andrisani, activists of the Osservatorio Migranti Basilicata, speculate, this experiment could have a potentially disruptive effect when spreading to other ghettos and threatening to break the power of the gangmasters. But they are quick to add that the latter are unlikely to be the instigators of this fire, because of the huge profits the ghetto generates for them.

In contrast to labour organisations, regional authorities continue to criminalise the place as hotbed of local mafia and gangmasters. Pietro Simonetti, coordinator of the regional task force on migration, who has repeatedly refused to meet Boreano’s inhabitants, commented that probably, the latter had received information of the imminent demolition of the labour camp. And so in concomitance with this decision someone decided to set the camp on fire. Without further ado, the coordinator also promised -unlike last year- to demolish the remaining habitats and host “those workers who are not illegal or working for a gangmaster” in the official host centres regional authorities have started to set up in cooperation with private organisations. Ironically, Simonetti used the term bonificare (disinfest, reclaim), which raises the impression he wants to rid the area of undesired habitants as if they were plants or animals.

In the meantime, the inhabitants of Boreano have decided to carry their struggle onwards. On Thursday about 50 labourers are meeting in Potenza in front of the Regional Palace to protest and bring their demands to the governor Marcello Pitella.

(c) Marc-Antoine Frebutte (2015)

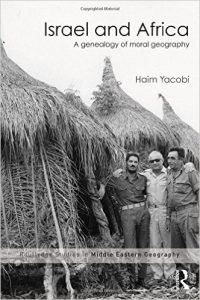

Particularly Yacobi’s discussion of the ‘Villa in the Jungle’ – a trope that highlights Israel’s moral geographic engagement with Africa, significantly informs this debate. ‘Walling off’ Eritrean refugees, he says, has not exclusively become a vector for reproducing Israel identity as set apart from Africa and the Middle East, but also reflects the persistent attempts of government authorities at active demographic engineering and urban segregation. The active exclusion of Eritrean churches thus has to be read in this context, of the racialisation of political space that characterises Israeli society as a whole.

Particularly Yacobi’s discussion of the ‘Villa in the Jungle’ – a trope that highlights Israel’s moral geographic engagement with Africa, significantly informs this debate. ‘Walling off’ Eritrean refugees, he says, has not exclusively become a vector for reproducing Israel identity as set apart from Africa and the Middle East, but also reflects the persistent attempts of government authorities at active demographic engineering and urban segregation. The active exclusion of Eritrean churches thus has to be read in this context, of the racialisation of political space that characterises Israeli society as a whole.