Society and Space just published a marvelous virtual theme issue on international migration, with contributions from Rutvica Andrijasevic and William Walters, Deirdre Conlon and my former colleague Susan Thieme, amongst others.

The collection adds further depth to the ongoing discussion in critical legal geography on the complex and expanding spaces of the law, expressed for example in a recent collection edited by Irus Braverman and others. These authors draw in turn on a long-standing scholarship of legal anthropologists like the Von Benda Beckmanns, Boaventura Santos, legal geographers like Nicholas Blomley and David Delaney, and legal scholars like Zoe Pearson and Oren Yiftachel.

In the guest editorial of Society and Space, called ‘the where of asylum’, Mustafa Dikeç asks the pugnant question:

“Does law produce spaces where it no longer applies? Does it, in other words, set up spaces of lawlessness?”

Parallel to Irus Braverman and colleagues, Dikeç addresses this question not merely from a practical legal perspective (how law is shaped) but out of a profound curiosity into power’s spatial constitution, as John Allen would put it.

What animates this growing body of work, Dikeç writes, is the idea that law may be involved in producing spaces of lawlessness. In other words: violence that is commonly depicted as ‘lawless’ may actually be committed through the law –or rather: through the continuous reproduction of its exception. It is this latter strand that seems to be the main concern of contemporary legal-spatial research.

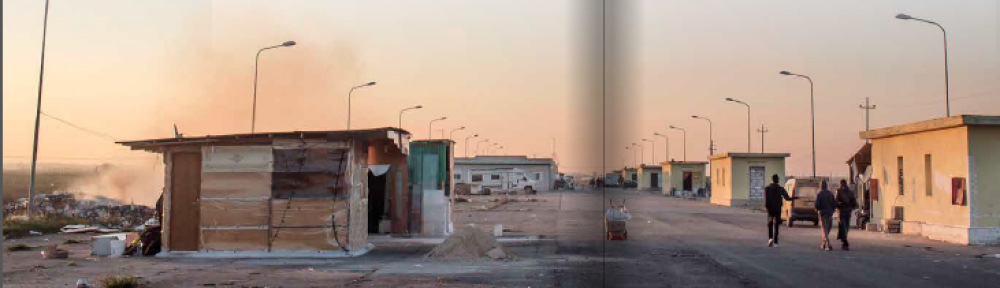

Dikeç’s question came to mind lately when watching a series of recent Italian documentaries on the expanding migrant ‘ghettos’ in Puglia, Campania and Basilicata (the issue is generating worldwide attention nowadays, some day I need to produce a list of recent contributions). Set up as labour camps for the numerous seasonal land labourers (or braccianti) who invigorate South Italy’s plantation economy, these ‘ghetto’s’ reflect the extremely violent and exploitative forms of encampment capitalist labour regimes engender across international borders today (not to speak about the strong semantic resonance of the term). But they also express how the law (particularly asylum law) consciously creates it own exception, which is henceforth placed outside of its protective realm.

In other words, the conscious abandonment of protection as a fundamental value of state sovereignty within the EU’s national state frameworks is not just made possible through the systematic prevention of access to its territory, or the official detention of migrants across Europe’s many camp sites. But it is also justified through the reproduction of these liminal environments, which simultaneously constitute the law’s outer-space – or frontier zone – and the inner space of cross-border capitalist undertakings. Reflecting on Europe’s schizophrenic hospitality, Andreas Oberprantacher writes:

It is crucial to realise, however, that it is not just states that are implicated in the creation and management of a heterogeneous population of illegal aliens, but also actors that are usually acting in concert with liberal democratic states, so that two major elements of the rule-of-law, that is jurisdiction and accountability, are effectively diffused in a rather viscous and all-too-often treacherous frontier regime.

Somebody who has been working on the transformation of the state’s legal space theoretically more recently is David Delaney. In his recent book, Nomospheric Investigations, he tries to overcome the discrepancy between the legal and the spatial as two autonomous realms. The nomosphere is the cultural-material environment that emerges out of the performative engagements through which the social signification of the ‘legal’ and the legal signification of the ‘social’ materialize and mutually constitute one another. At the same time Delaney makes it plain that nomic settings, like the home, the archive, or the workplace, do not exist in isolation from one another. But they are the contingent products of pervasive cultural processes associated with the nomosphere (he uses the term nomoscapes). His work feels reminiscent of feminist scholarship about the location of knowledge (I think of Donna Harraway and Bell Hooks for example) as well as some of the more recent critical scholarship on borders (of which the Society and Space theme issue is just one recent outcome) I look forward to engage more in-depth with.